COLCHESTER (Essex).

COLCHESTER (Essex). Gules, two staves raguly and couped argent, one in pale, surmounted by another in fesse between two ducal coronets in chief or the bottom part of the staff enfiled with a ducal coronet of the last.

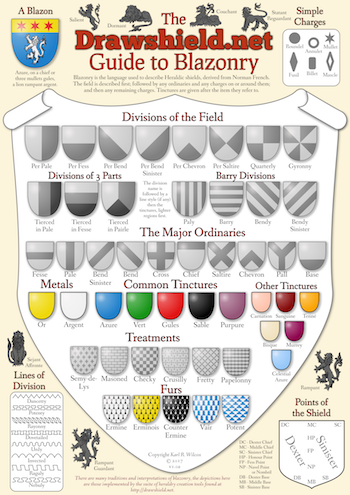

[Recorded in the College of Arms (see Fig. a).]

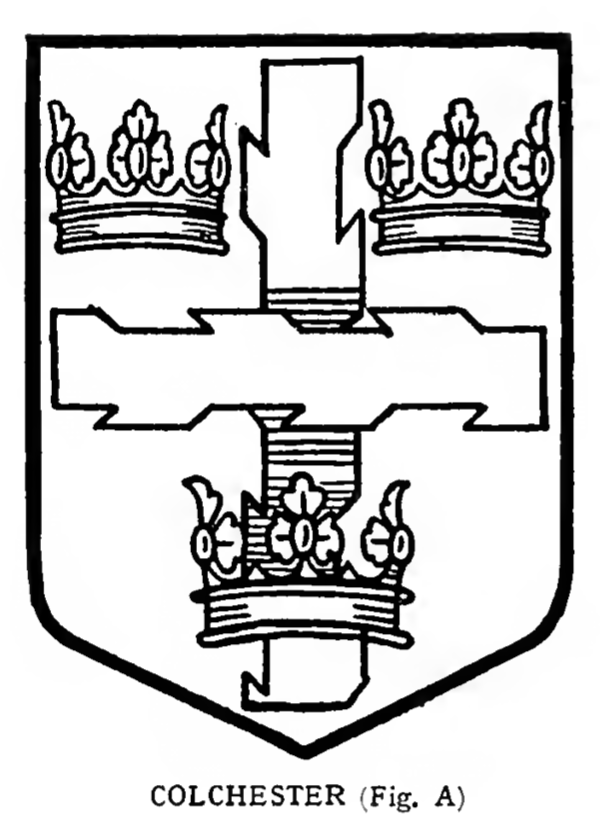

On 3rd March 191 5 the Corporation of Colchester considered a report by Alderman Benham concerning the arms of the Borough, which drew attention to their emblazonment on the Letters Patent granted to Colchester, 7th July 141 3, by King Henry V., this being the earliest known example of them, and in pursuance of a motion by the Alderman it was resolved to revert to the original form as appearing upon the Letters Patent " and as also employed upon the Common Seal of the Borough, adopted at about the same date, and used continuously as the Borough Seal for over four centuries."

As will be seen from the illustration (Fig. B), the difference consists of the method of the intersection of the limbs of the cross and the introduction of three nails therein below the crowns. It is, of course, possible the nails were originally constituent parts of the arms, but knowing the licence claimed in early times by heraldic artists, and considering the character of the emblazonment upon the

charter, the probabilities seem rather in favour of these alleged differences being no more than artistic elaboration of the arms by an ecclesiastic to emphasize the legend of their origin.

[Refer to "The Essex County Standard," 6th March 191 5, and "The Essex Review," January 1914.]

Is it simply a coincidence that these arms are identical with those of the town of Nottingham (except that in the latter case the staves are vert), or is there some connection ? The arms of Colchester are frequently quoted wrongly as "gules two staves raguly and couped argent one in pale surmounted by another in fesse between four ducal coronets or." The following newspaper cutting records a legend which has evidently been accepted in the designing of the present seal of the Corporation. I give it for what it is worth : —

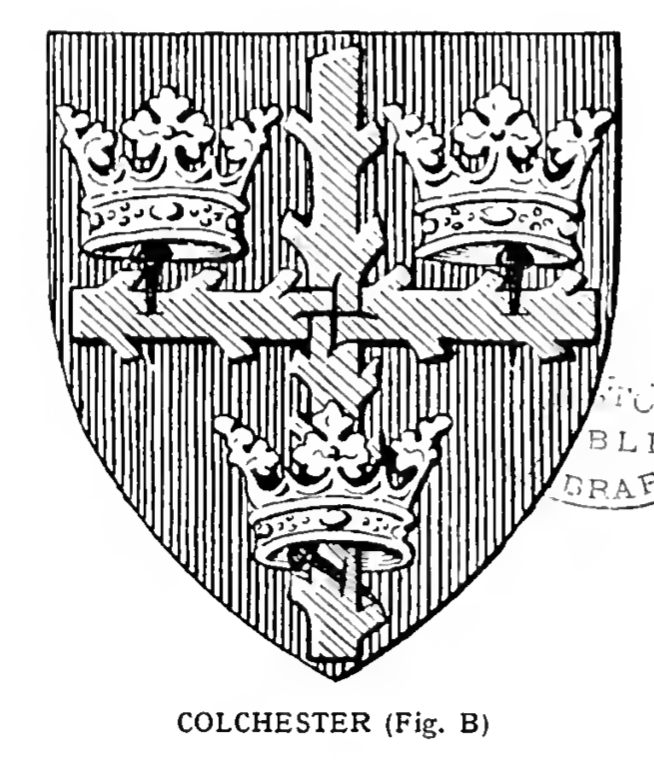

" Colchester offers us a remarkable escutcheon ; no less remarkable is the story attaching to it. We shall at once recognise the cross with branches or enragled, as heralds term it [they don't; they call it ' ragulcd ' or 'raguly' — Ed.] with four crowns in the angles. This is a token of the discovery of the true cross by the Empress Helena, who was a native of Britain, and is said to have been the daughter of Coel, a British chieftain whose territor}' was adjacent to Colchester. St Helena married Constantius, and was the mother of the great Christian Emperor Constantine, who caused her to be proclaimed Empress. She was not converted to the Christian faith till she was about sixty years old. At this age she undertook a journey to the Holy Land, and on her arrival at Jerusalem she was seized with the desire of finding the true cross. She was informed that she would be able to do this if she could discover the holy sepulchre where Christ had been laid, as the Jews were accustomed to bury the instruments of punishment near the grave of the person who had suffered. Now the heathens had, out of aversion to the Christian religion, raised a mound over the place of our Saviour's entombment, and had built a temple to Venus upon it, so that those who visited the holy places out of devotion to Christ might appear to be paying homage to a pagan deity. The Empress, however, ordered excavations, and the result was that three crosses were found. It was, however, quite uncertain still which cross was the one upon which the Saviour had been crucified. An ancient legend tells how this was determined. There happened to be at the time in Jerusalem a lady who was lying dangerously ill. It was decided to ask a sign from heaven by which the true cross of Christ might be recognised, and all the Christian community of Jerusalem joined in prayer for this object. One of the crosses was allowed to touch the sick lady. Nothing, however, ensued. Another cross was applied to her with a similar result. At last the remaining cross was brought to her bedside, and the invalid had scarcely touched it ere she was completely restored to health and strength. The last cross was therefore immediately recognised as the real cross, and was by the Empress's order enclosed in a case of silver and preserved in a magnificent church built to receive it."

Original Source bookofpublicarms00foxd_djvu.txt near line 7181.

Please Help!

DrawShield is a Free service supported by its users.

If you can, please help cover the cost of the server, or just buy the team a coffee to say thanks!

Buy me a coffee

Buy me a coffee